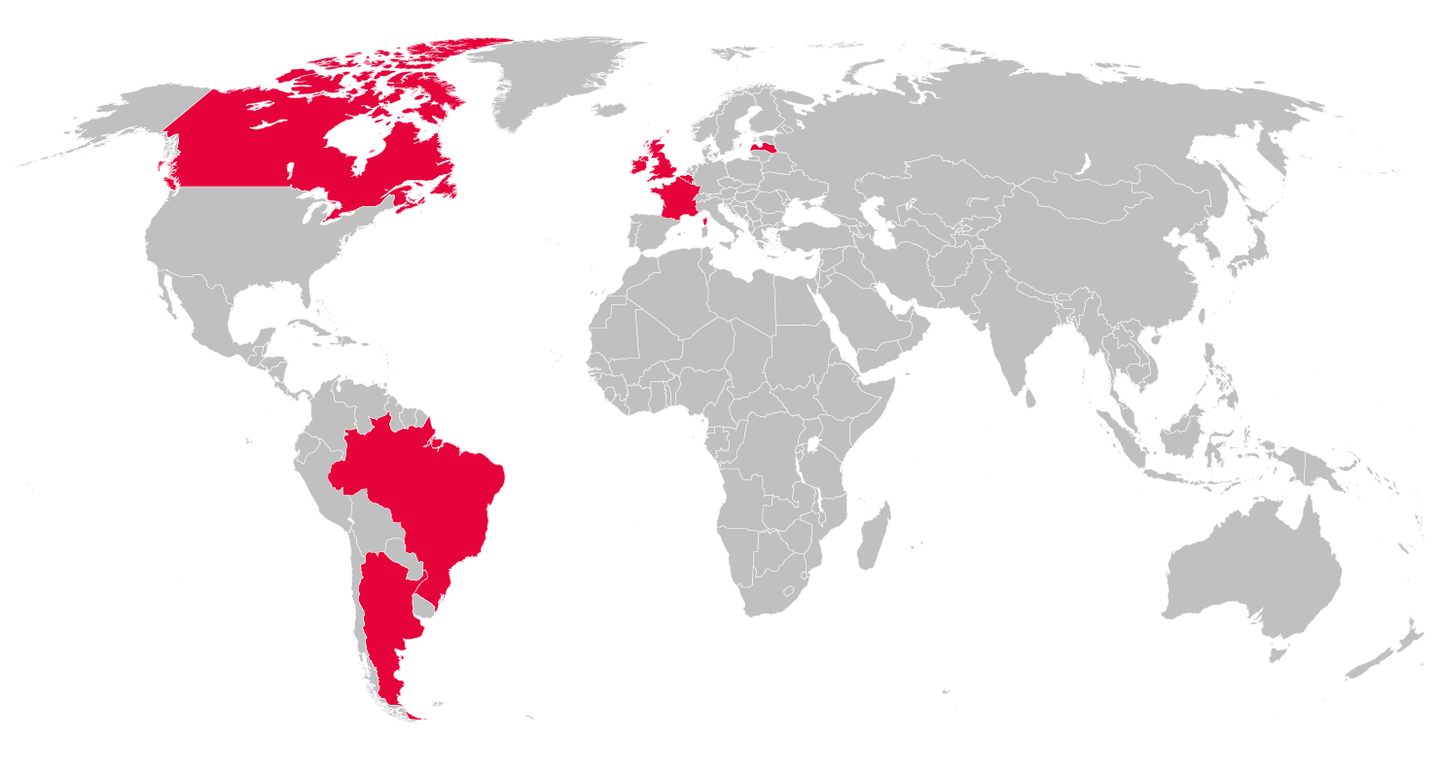

In November 2018, representatives from eight countries joined the United Kingdom’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee for a meeting known as an “International Grand Committee” (IGC), to discuss the spread of disinformation, the threat of “fake news,” questions of privacy and about protecting individuals’ data — and what this all means for democracies around the world.

The idea of an IGC arose from a meeting in a Washington pub between four members of Parliament (MPs) — the United Kingdom’s Damian Collins and Ian Lucas, and Canada’s Bob Zimmer and Nathaniel Erskine-Smith. Over beers, as Zimmer recounted earlier this year, they discussed bringing together international colleagues of various countries to tackle the challenges facing societies in the digital age. “We wanted to do something better — we thought better together as a coalition of countries to work out some solutions to these problems,” Zimmer said.

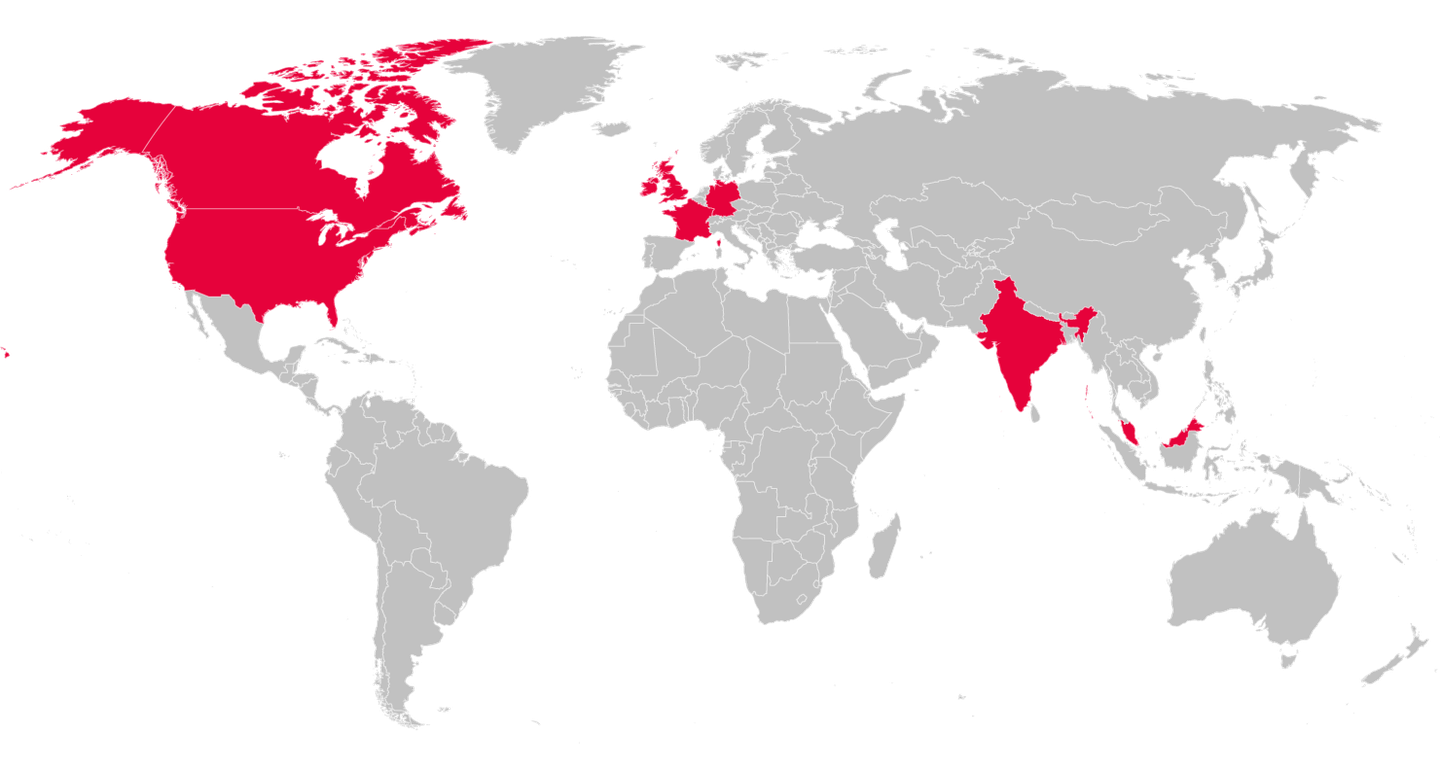

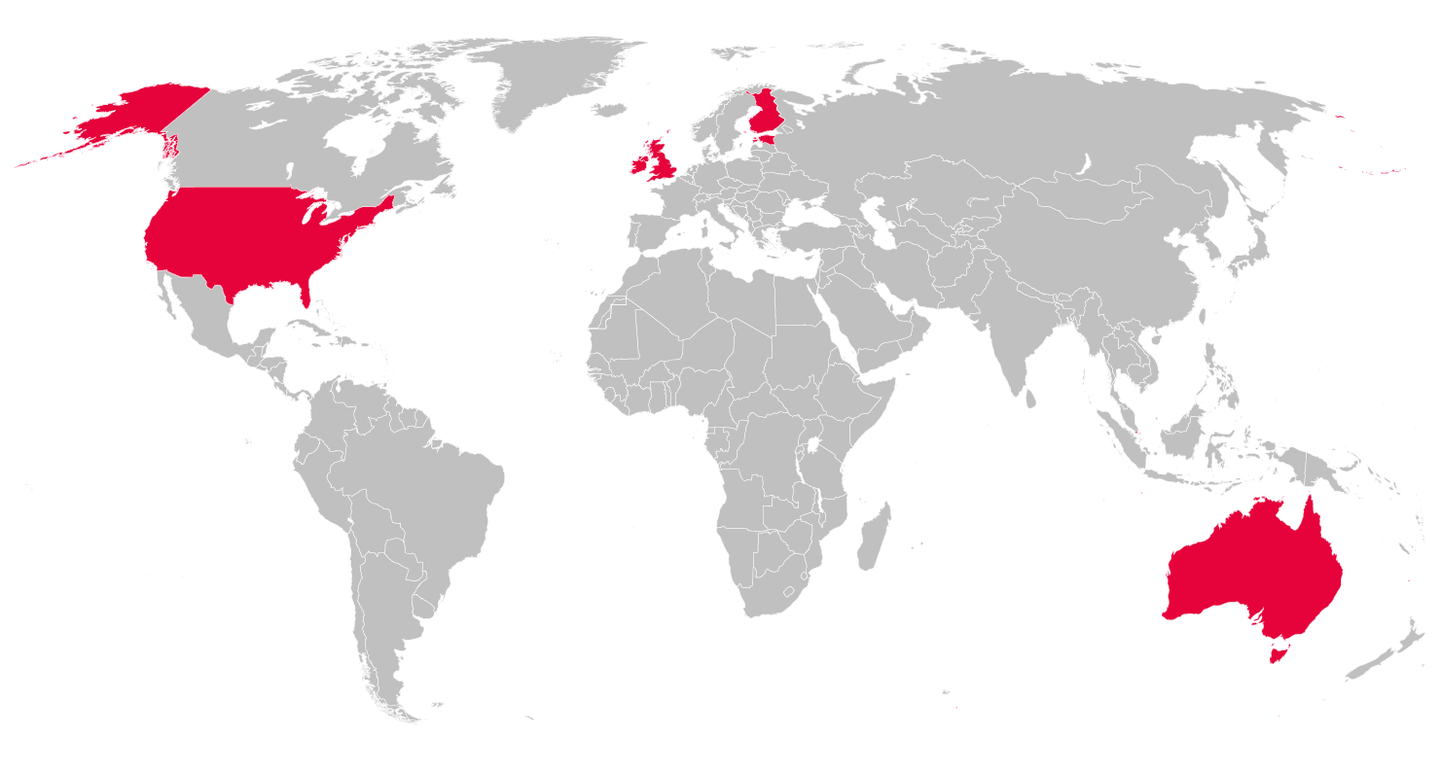

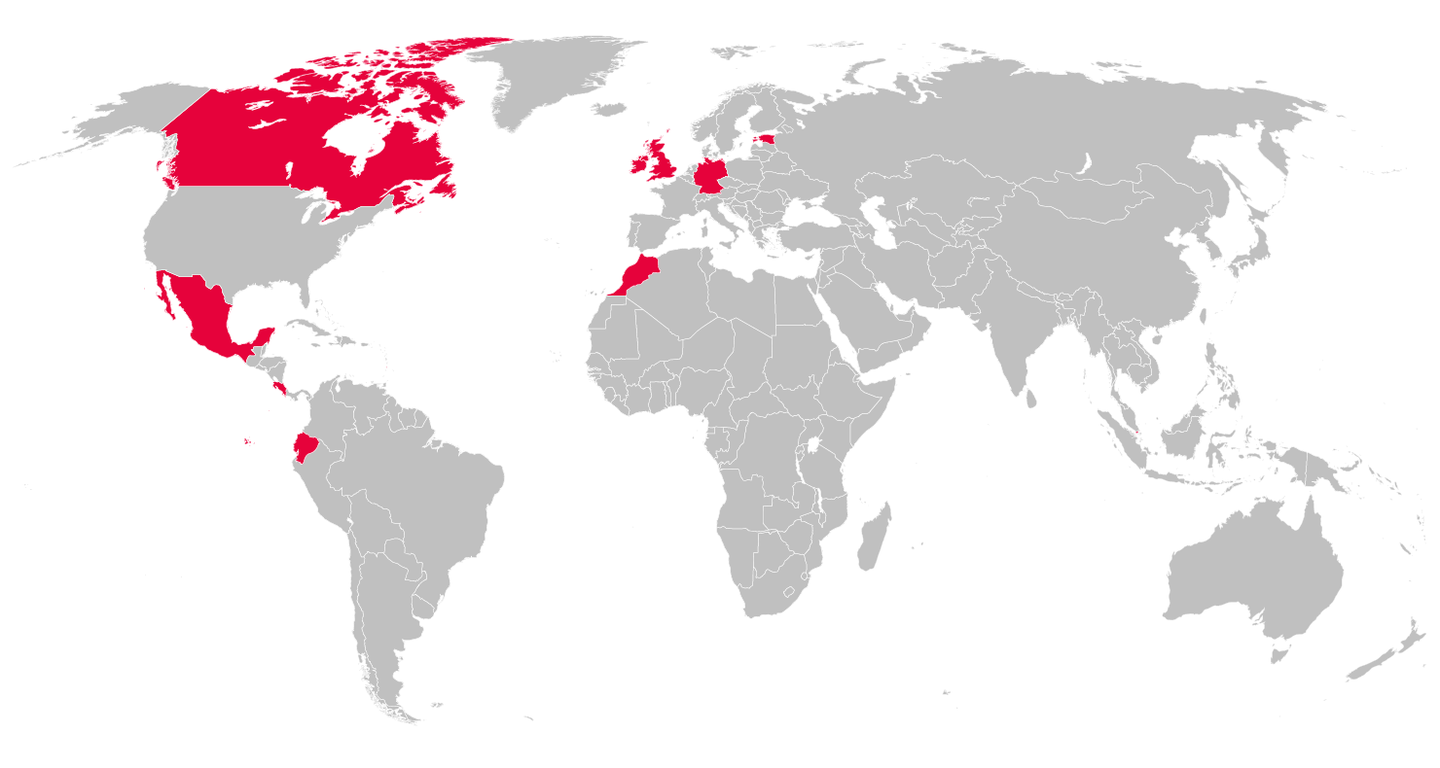

The inaugural session of the IGC on Disinformation and “Fake News” took place on November 27, 2018, in London. In 2019, Ottawa hosted the second session May 27–29 (with a slightly amended name: the IGC on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy); Dublin hosted the third session on November 7. In 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, the committee, now the IGC on Disinformation, postponed planned in-person hearings in favour of three short virtual events during the summer, co-hosted with the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics at The George Washington University (GWU). In early December 2020, the co-hosts reconvened to present “IGCD4,” two 90-minute online sessions attended by policy makers from across the globe.

In 2019, Shoshana Zuboff, author of The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power and one of the witnesses at the Ottawa hearing, spoke to CIGI about how vital she considers the work of the IGC to be. “Right now this is the only international body that grasps surveillance capitalism and its consequences as a critical threat to the future of democracy,” she said during an interview that August. For Zuboff, this is an important opportunity for parliamentarians and law makers to rein in the unintended consequences of big tech and digital platform companies.

For those wishing to get up to speed on the IGC, we’ve compiled summaries of each meeting, including audio testimony, transcripts and video recordings.

In 2020, amid a raging pandemic and the most fiercely contested presidential election in generations, many Americans were relying on largely unregulated digital platforms for their “news” — often from sources with stakes in stoking confusion, spreading disinformation and inciting hatred. As the year drew to a close, participants in two 90-minute online meetings co-hosted by the IGC and GWU’s Institute for Data, Democracy, and Politics discussed how these and related issues have been playing out and affecting their own domestic jurisdictions, along with their countries’ responses.

On the first day, parliamentarians met for a private “2020 Disinformation Review.” They reconvened the next day for a video conference open to the public and media, “Next Steps for Platform Regulation.” Several members of the IGC who have conducted investigations and are developing legislation spoke on a wide range of platform governance topics, including antitrust and taxation issues, privacy by design, algorithmic blackboxes and biases, problems embedded in apps’ terms of service and issues of consent, the infodemic, “cyber hit squads,” electoral integrity and manipulation of election campaigns. They also spoke of their own governments’ challenges and efforts in developing policies for reforms to address these problems. In the last few minutes they addressed questions from media and described some of the practical ways in which IGC members’ collaboration is helping to inform and drive efforts toward a collective approach to platform governance.

Committee members, experts and industry representatives met for a day-long meeting, focusing specifically on how to advance international cooperation when regulating hateful and harmful online content, as well as content that seeks to interfere in elections.

For a third time, Zuckerberg declined to appear before the committee; in his place was Monika Bickert, Facebook’s vice president of content policy.

The day’s discussion centred on several questions: What most urgently needs to be addressed when it comes to the harm caused by hate speech and electoral interference online? What regulatory structures exist to address these issues, and what will they look like going forward? How can national parliaments work together on platform regulation?

On November 7, 2019, the seven countries represented at the meeting agreed to a set of principles “to advance international collaboration in the regulation of social media to combat harmful content, hate speech and electoral interference online.”

The nine principles are as follows:

- Online harmful content and disinformation are complex problems which require political and civic collaboration to combat; left unchecked, these problems will undermine our civic space and democratic institutions.

- The work of the International Grand Committee has proven valuable in highlighting the issue of disinformation and desires this work to continue.

- The Committee continues to recognise the conflicting principles that sometimes apply to the regulation of the internet, including the aim to protect freedom of speech, in accordance with national laws, while, at the same time, countering abusive speech and disinformation.

- There is need for full transparency regarding the source, targeting methodology and levels of funding for all online political advertising but such controls should not be interpreted as a blanket ban on advertising relating to the political sphere.

- The Committee believes that global technology firms cannot on their own be responsible in combatting harmful content, hate speech and electoral interference and that self-regulation is insufficient.

- Technology companies should be fully accountable and answerable to national legislatures and other organs of representative democracy.

- The internet is global and accordingly it is vital that an internationally collaborative approach is taken with regard to regulation.

- The Committee recognises the initiatives taken by individual countries and non-governmental organisations in this space, but these require more co-ordination across national boundaries.

- The Committee therefore recognises the need for a dedicated international space which provides such co-ordination of internet regulations and commit to work with governments and relevant multilateral organisations in the establishment of such governance structures.

The committee also recommended a moratorium on online micro-targeted political advertising containing false or misleading information.

Over the course of three days, the committee asked questions of and heard testimony from experts and academics, as well as representatives from major tech companies, including Facebook, Google and Twitter. Witnesses discussed the effects of technology and social media platforms on the way consumer data is manipulated; the challenges these effects present to privacy; and the need for international coordination to prevent a breakdown of democracy.

Both Zuckerberg and Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg declined to appear before the committee; as a result, a motion was adopted by the committee to serve Zuckerberg and Sandberg with a formal summons to appear before the next meeting, should either travel to Canada in the future.

On May 28, 2019, the 11 countries represented at the meeting signed a Joint Declaration “reaffirming their commitment to protecting fair competition, increasing the accountability of social media platforms, protecting privacy rights and personal data, and maintaining and strengthening democracy.” Members signalled their intent to continue the committee’s work with these objectives in mind.

On June 18, 2019, Canada’s Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics published its report, International Grand Committee on Big Data, Privacy and Democracy, summarizing the previous month’s three-day testimony.

During the meeting’s first hearing, parliamentarians grilled Facebook Vice President of Policy Solutions Richard Allan about the Cambridge Analytica scandal, how personal data is shared via Facebook’s apps, Russian activity on the social network, and more. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg had been invited to appear before the committee but had declined, leading MPs — who didn’t try to mask their frustration — to put out an empty chair to highlight his absence.

In the afternoon, the committee spoke with the United Kingdom’s information commissioner, Elizabeth Denham, and her deputy, Steve Wood. Questions and testimony were centred around what tools might be useful for law makers to be able to constrain “data mercenaries” such as AggregateIQ, how to ensure regulators have “teeth,” what kind of framework should be created to guard against disinformation, and more.

There was also a surprise appearance by Ashkan Soltani, the former chief technologist of the US Federal Trade Commission. Soltani decided last-minute to speak to the committee after taking issue with Allan’s testimony around the access to data granted to third-party developers via Facebook apps.

On November 27, 2018, the nine countries represented at the meeting signed a Declaration noting that “it is an urgent and critical priority for legislatures and governments to ensure that the fundamental rights and safeguards of their citizens are not violated or undermined by the unchecked march of technology.”

The representatives declared and endorsed five principles, stating:

- The internet is global and law relating to it must derive from globally agreed principles;

- The deliberate spreading of disinformation and division is a credible threat to the continuation and growth of democracy and a civilising global dialogue;

- Global technology firms must recognise their great power and demonstrate their readiness to accept their great responsibility as holders of influence;

- Social Media companies should be held liable if they fail to comply with a judicial, statutory or regulatory order to remove harmful and misleading content from their platforms, and should be regulated to ensure they comply with this requirement;

- Technology companies must demonstrate their accountability to users by making themselves fully answerable to national legislatures and other organs of representative democracy.

On February 18, 2019, the United Kingdom’s Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee released a final report on its inquiry into disinformation and “fake news,” the result of information received over 23 oral evidence sessions and more than 170 written submissions over 18 months. The report lists 51 conclusions and recommendations for seven areas: regulation and the role, definition and legal liability of tech companies; data use and data targeting; the relationship between Canadian tech firm AggregateIQ and Cambridge Analytica; advertising and political campaigning; foreign influence in political campaigns; the influence of SCL Group (Cambridge Analytica’s parent company) in foreign elections; and digital literacy.